10. Counter/Catholic-Reformation in 1500s

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 1506 | Francis Xavier, co-founder of the Jesuits and Catholic missionary, born

|

| 1513 | Leo X becomes Pope (a member of the Medici family, Leo is head of the Catholic Church during the turbulent years 1513-1521)

|

| 1521 | Luther is excommunicated

|

| 1540 | Jesuit order is founded

|

| 1545 | The Council of Trent begins (concludes in 1563)

|

| 1553 | Mary Tudor begins her reign in England; many Protestants flee Mary's reign

|

| 1555 | Peace of Augsburg, after chronic conflict, the first permanent legal basis for the existence of Lutheranism as well as Catholicism in Germany

|

Context and Impact of the Reformation

The events and change of thinking that the Reformation gave rise to signalled the gradual end of

the Middle Ages and the beginning of modern times.

Historians refer to the period spanning the 14th to the 17th centuries, which were marked by a

revival of art (Leonardo da Vinci, Rafael, Michelangelo), architecture, music and literature

(Machiavelli, William Shakespeare, Miguel de Cervantes) cultural expressions, exploration in the

New World and Asia (Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, Francis Drake), and new ways of

looking at the world (Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler) as the "Renaissance"

(lit "re-birth"). This was the context of the Reformation.

The Reformation brought about two different streams of Christianity - the established (now

called "Catholic", or Roman Catholic) Church and emerging Protestant churches/cities. It

changed the religious beliefs, practises, culture and society of Christians in Europe. It divided

Christian communities and reshaped political and religious values. It challenged the authority of

the Popes over rulers (Kings gained absolute control over their kingdoms). It also led to antiauthoritarianism,

resulting in contempt for the feudal system and the power of the feudal lords,

and a preference for government by the people.

Consider some of the differences:

"True Church"

- Catholics believed they constituted the only true church - a belief held until the 20th

century (and still held by some)

- Protestants believed that salvation lies in justification by faith, not which church

tradition or structure people belong to

Church Services and the Bible

- Catholics believed that Church services and the Bible should be in Latin, as they had been for 1000 years

- Protestants believed that church services and the Bible should be readily accessible and understandable, in the language/s of the common people

Priests

- Catholics believed that priests were links between God and people and that the Pope was

ordained by God. Priests were expected to devote their lives to God, remain unmarried

and wear clerical robes

- Protestants believed that people could find God without a priest/Pope and that

Ministers should lead normal lives and wear ordinary clothes

Sins

- Catholics believed that priests and the Pope were able to forgive sins - sometimes at a

price.

- Protestants believed that only God can forgive sins

Churches

- Catholics believed that churches celebrate God, and decorated places of worship with

statues and shrines

- Protestants believed that churches should be plain. In parts of Europe

monasteries were dissolved and assets taken over by the aristocracy or given to

common people (who then supported the changes). The destruction of religious

symbols on ideological grounds ("iconoclasm") became widespread; altars,

shrines, statues and stained glass windows were destroyed.

Authority Structures

- Catholics believed that ultimate authority in the church on earth rested with the Pope.

- Protestants believed that authority lay with local leadership. Kings and

aristocrats assumed authority/autonomy they did not have under Catholic rule.

It should be remembered that the original leaders of the Reformation were born, baptized,

confirmed and educated in the (Roman Catholic) Church, and most of them served as priests,

with vows of obedience to the Pope. Some remained in the Catholic Church until they died.

To complicate matters, the Reformers did not always agree with one another in their

doctrines/approaches to authority and structure. While they agreed over the essential matters

of the gospel, they disagreed over church leadership, the Lord's Table, and the relationship of

the church to the state. Many Protestant denominations developed, and they were organized in

a variety of ways; Catholic historians interpret this as a sign that the unity of the Catholic

Church proved that it was the authentic church.

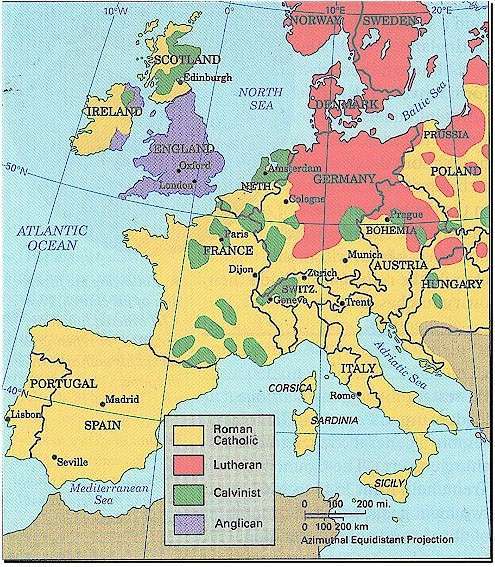

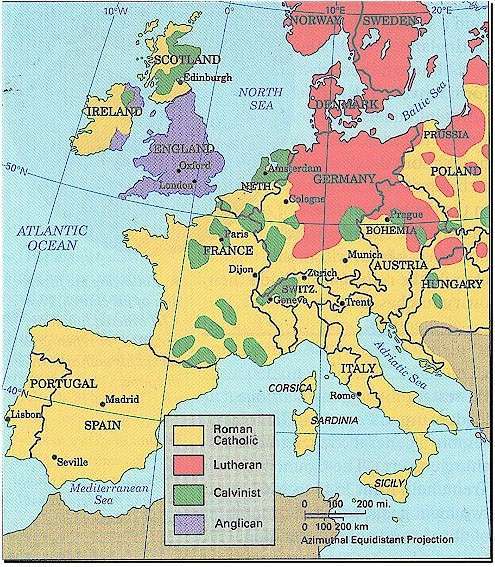

Europe (and Western Christianity) was now divided between Catholic countries of the south and

Protestant countries of the north (while Europe today is more secular, those dividing lines

continue to exist). In parts of Europe, this diversity of religious life created a mood of religious

toleration and a respect for the importance of the individual conscience. The Reformation

stimulated many internal reforms. The Church gained new purity and strength during the late

1500s and the 1600s through the Counter Reformation. In other parts of Europe the diversity

led to major conflict.

For example, the Thirty Years War (1618-48) was fought by various nations for religious,

dynastic, territorial, and commercial reasons. Its destructive campaigns and battles occurred

over most of Europe, and, when it ended with the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), the map of

Europe had been irrevocably changed.

The Inquisition (Holy Office), founded in the 13th century, expanded its activities and "heretics"

were subject to punishment, torture and death. This had a deterrent effect against the spread

of Protestantism. Bear in mind that where Protestantism gained official status -- England,

Scotland, Geneva, Germany, and Scandinavia -- Catholics were also persecuted.

Loyola and the Jesuits

Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556), a Spaniard, was originally a soldier, who was wounded in battle and

experienced a religious conversion. After becoming a monk, he who sought to create a new,

disciplined religious order by fusing Renaissance humanism with a reformed Catholicism that he

hoped would appeal to powerful economic and political groups now attracted to Luther and

Calvin. To many in the Church, Loyola was the embodiment of the Catholic Reformation.

Founded in 1534, the Society of Jesus or the Jesuits formed the backbone of the Counter

Reformation. The Jesuits combined the ideas of traditional monastic discipline with a

dedication to teaching and preaching. They sought to bypass local corruption by not attaching

themselves to local bishops or church/secular authorities. The Jesuit society demands four vows

of its members: poverty, chastity, obedience to Christ, and obedience to the Pope. The purpose

of the Jesuits is the propagation of the Catholic faith by any means possible.

As theologians, the Jesuits focussed on Protestant theology about predestination. Predestination

seemed to offer hope of salvation for the literate and prosperous and reserve doom, despair and

the abyss for others. The Jesuits promised hope, based on familiar ceremony, and tradition in

the power of the priest to offer forgiveness. They urged princes to strengthen the Church in

their territories. They developed the theology that permitted "small sins" in the service of a just

cause, in other words, a small sin was excusable if it led to some greater good.

By the 17th century, Jesuits had become some of the greatest teachers in Europe and had

missionaries in the Americas, Asia and Africa (including as part of European colonialism and to

counter Protestantism). They had become one of the most controversial and upwardly mobile

religious groups within the Church. Was their order a disguise for political power? Were they

the true voice of a reformed Church? The Jesuits helped build schools and universities, design

churches and even helped produce a unique style of art and architecture. The goal of spreading

the Catholic faith is still their primary objective, and they do it through missionary work and

education. The influence of the Jesuits continues. Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott

attended primary school at St Aloysius' College at Milson's Point, Sydney, before completing his

secondary school education at St Ignatius' College, Riverview (both are Jesuit schools).

Francis Xavier (1506-1552)

Missionary Francis Xavier was from a Spanish Basque noble family. When Francis met Ignatius

Loyola in Paris he was a proud, autocratic, ambitious man wanting to accomplish great things.

For three years Ignatius encouraged Francis to look at his life differently. "What profits a man,"

Loyola asked Francis (quoting Jesus), "if he gains the whole world and loses his soul?" Francis

joined Loyola as a monk in 1537.

In 1541 King John of Portugal asked Ignatius for priests to send as missionaries to India. Francis

arrived at Goa in 1542. During the next ten years he travelled from Goa to Cape Comorin in

south India, then to the East Indies, Malacca, and the Moluccas, and on to Japan. It was his

ambition to get permission to enter China as a missionary. He died in China in 1552, exhausted

from his labours and fasts. He is buried in Goa, India.

Francis Xavier's ambition was to bring the world to Jesus Christ. He preached the Gospel to the

poor and sick. His nights were taken up in prayer. His only attention to his personal needs was

to have a pair of boots. He barely ate enough to stay alive. After his death, he left behind

churches that were the foundations for the Catholic faith in Asia.

"Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man." (Francis Xavier)

The Council of Trent

The Reformation demonstrated the need for reformation of the Church, in light of widespread

abuses by Church leadership over the previous hundred years.

The 19th ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church (held at Trent, Italy, from 1545-63)

was important for its decrees on reform and for its definitions that clarified virtually every

doctrine contested by Protestants. Despite internal strife, external dangers, and interruptions,

the Council played a vital role in revitalizing the Roman Catholic Church in many parts of

Europe. Along with the part played by the Jesuits, the Council was a central feature of the

Counter-Reformation. But whether Trent represented a positive move remains doubtful.

The Council was called by Paul Ill (Pope from 1534 to 1549) and first sat in December 1545. The

pope did not attend the meetings of the Council and had no formal part in it. But his

representatives ensured that the pope's views would always be put forward.

Any long term change in the Church depended on the attitude of the pope in power at the time.

If there was no desire for change, then there would be no change. Julius III (1550 to 1555)

showed little interest in reform. Some popes were interested in moving forward the Church, eg

Sixtus V (1585 to 1590). Most of the popes did not wish to lose power and did not feel

enthusiasm for the abolition of established practices.

700 bishops could have attended the Council but to start with only 31 turned up along with 50

theologians. By 1563, a total of 270 bishops attended and the vast majority of them were Italian

which was a great bonus for the pope as they were under his control and it was the pope who

effectively controlled promotion to cardinal etc. and these men would not be seen in public

doing anything other than what the pope wanted. The bishops also insisted that they vote as

individuals rather than as a block-country vote and as there were 187 Italian bishops, 32 Spanish,

28 French and 2 German the Italians vastly outnumbered the other three countries put together.

As such what was to be passed at Trent was what the pope accepted.

The Council had been called to examine doctrine and reform. Charles V had wanted abuses

looked at first in an attempt to please the Protestants and hopefully tempt them back to the

church. Once they were back they could look at doctrine. Paul III did not want this as reforms

could financially damage him and concessions could diminish his authority. The result was that

two separate sections dealt with reform and doctrine simultaneously.

Results of the Council of Trent

Period I (1545-47): When a crisis developed as the Council opened (some urging immediate

reform and others urging clarification of doctrines), a compromise was reached: both were to be

treated simultaneously. The council then laid the groundwork for future declarations:

- the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed was accepted as the basis of Catholic faith;

- the canon of Old and New Testament books was fixed;

- tradition was accepted as a source of faith;

- the Latin Vulgate was declared adequate for doctrinal proofs;

- the laity would be required to accept the official interpretation of the Scriptures;

- the number of sacraments was fixed at seven (Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist,

Penance, Anointing of the Sick, Matrimony, and Holy Orders; the sacraments were

considered essential for salvation);

- the nature and consequences of original sin were defined;

- the Council ruled against Luther's doctrine of justification by faith alone: man, the

Council said, was inwardly justified by "cooperating with divine grace" that God bestows

(code for good works).

Political problems forced the Council's transfer to Bologna.

Period II (1551-52): Before military events forced a second adjournment of the council, the

delegates finished an important decree on the Eucharist that defined the Real Presence of Christ

in opposition to the interpretation of Zwingli, the Swiss Reformation leader, and confirmed the

doctrine of Transubstantiation.

- the sacrament of penance was extensively defined;

- extreme unction (later, the anointing of the sick) was explained;

- decrees were issued on episcopal jurisdiction and clerical discipline.

German Protestants, some of whom were welcomed at meetings of the Council (though many

refused the invitation), meanwhile, were demanding a reconsideration of all the council's

previous doctrinal decrees and wanted a statement asserting that a council's authority was

superior to that of the pope.

Period III (1562-63): Pope Paul IV (1555-59) was opposed to the council, but it was reinstated by

Pius IV (1559-65). The arrival of French bishops (who had largely boycotted earlier meetings of

the Council) reopened the explosive question regarding the divine basis for the obligations of

bishops to reside in their sees.

- the council defined that Christ is entirely present in both the consecrated bread and the

consecrated wine in the Eucharist (Transubstantiation) but left to the pope the practical

decision of whether or not the chalice should be granted to the laity;

- defined the mass as a true sacrifice;

- reaffirmed the doctrine of justification through faith and works;

- issued doctrinal statements on holy orders, celibacy of clergy, purgatory, indulgences,

and the veneration of saints, images, and relics (but condemned abuses in the sales of

indulgences);

- re-affirmed the ultimate authority of the Pope;

- enacted reform decrees on clerical morals and the establishment of seminaries.

What were the theological lessons of the Counter-Reformation?

Interpreting the Reformation demands an understanding of the Catholic response. The Council

addressed a number of issues of ecclesiastical abuse. The education of priests was improved.

Discipline and orthodox teaching were tightened. The Church expanded its missions effort (in

line with the age of exploration and settlement of overseas colonies), to prevent Protestants

from expanding their own authority/influence; large numbers of Catholics in the Americas,

Africa, India, Japan and Sri Lanka owe the strength of the Church to the Catholic Reformation.

Protestants were disappointed with the outcomes of the Council; reconciliation/reunification

was ruled out. The Reformation led to the division of Europe along cultural lines that are strong

even today.

The Reformation had contributed to the establishment of an ethic of individualism. Protestants

were able to interpret the Bible for themselves. They made their own decisions that resulted in

salvation or eternal death.

After 1520, the official Church was quick to censor and burn books ("heretical literature") that

might have spread the Protestant faith. Protestant books were burned; so too were works of

reform-minded Catholic humanists including Petrarch and Erasmus. The Index of Prohibited

Books became an institution within the Church and was not abolished until 1966. The work of

the Inquisition continued throughout much of Europe.

Ongoing attempts were made to bring the whole of Europe back under the authority of the

Church and Pope. The (unsuccessful) Spanish Armada of 1588 against England was an example of

an attempt to re-assert Catholicism, in England. Philip II of Spain was the son of Emperor

Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and cousin/husband of Mary and followed a sustained period

of persecution of Protestants in England. English Bishops Ridley and Latimer had been burned at

the stake in 1555 for denying Transubstantiation and the sacrifice of the Mass; 268 clergy had

been executed for being Protestants. Acts of Parliament against heretics had been repealed

under Elizabeth I; the Spanish and the Church had refused to recognise the legitimacy of

Elizabeth. The intention of the Armada was to end the rule of Elizabeth and install a new

Catholic monarch.

Issues Facing Christians During this period

- What was the ultimate source of spiritual authority?

- Could the Christian community be independent of secular rule, politics and practices?

- Was it better to remain in the official Church and try to change things from the inside?

- Could those who remained in the established church hold to the Gospel?

- How could the reform movement remain united?

- Could Christian communities be viable without an "Apostolic line"?

- How could faith in an unseen God survive in the context of increasing secularism and

skepticism of the Renaissance?

Reading

Blainey, G, A Short History of Christianity, Viking, Melbourne, 2011

Lion, A Lion Handbook, 1990, The History of Christianity

Miller, A, Miller's Church History: From the First to the Twentieth Century

Renwick, AM, The Story of the Church, Intervarsity Press, Edinburgh, 1973

Wright, J, The Jesuits: Missions, Myths and Histories, Harper Perennial, London, 2005

Jesuit Missions

Early missions in Japan resulted in the government granting the Jesuits the feudal fiefdom of

Nagasaki in 1580. However, this was removed in 1587 due to fears over their growing influence.

Francis Xavier, one of the original companions of Loyola, arrived in Goa, in Portuguese India, in

1541 to consider evangelical service in the Indies. In a 1545 letter to John III of Portugal, he

requested an Inquisition to be installed in Goa (see Goa Inquisition). He died in China after a

decade of evangelism in Southern India. Two Jesuit missionaries, Johann Grueber and Albert

Dorville, reached Lhasa in Tibet in 1661.

Jesuit missions in America were very controversial in Europe, especially in Spain and Portugal

where they were seen as interfering with the proper colonial enterprises of the royal

governments. The Jesuits were often the only force standing between the Native Americans and

slavery. Together throughout South America but especially in present-day Brazil and Paraguay,

they formed Christian Native American city-states, called "reductions" (Spanish Reducciones,

Portuguese Reduções). These were societies set up according to an idealized theocratic model.

It is partly because the Jesuits, such as Antonio Ruiz de Montoya, protected the natives (whom

certain Spanish and Portuguese colonizers wanted to enslave) that the Society of Jesus was

suppressed.

Jesuit priests such as Manuel da Nóbrega and José de Anchieta founded several towns in Brazil in

the 16th century, including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and were very influential in the

pacification, religious conversion and education of Indian nations.

Jesuit scholars working in foreign missions were very important in studying their languages and

strove to produce Latinized grammars and dictionaries. This was done, for instance, for

Japanese (see Nippo jisho also known as Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam, (Vocabulary of the

Japanese Language) a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary written 1603), Vietnamese (French Jesuit

missionary Alexandre de Rhodes formalized the Vietnamese alphabet in use today with his 1651

Vietnamese-Portuguese-Latin dictionary Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum) and

Tupi (the main language of Brazil). Jean François Pons in the 1740s pioneered the study of

Sanskrit in the West.

Under Portuguese royal patronage, the order thrived in Goa and until 1759 successfully

expanded its activities to education and healthcare. In 1594 they founded the first Roman-style

academic institution in the East, St. Paul Jesuit College in Macau. Founded by Alessandro

Valignano, it had a great influence on the learning of Eastern languages (Chinese and Japanese)

and culture by missionary Jesuits, becoming home to the first western sinologists such as Matteo

Ricci. On 17 December 1759, the Marquis of Pombal, Secretary of State in Portugal, expelled the

Jesuits from Portugal and Portuguese possessions overseas.

Jesuit missionaries were active among indigenous peoples in New France in North America.

Many of them compiled dictionaries or glossaries of the First Nations and Native American

languages which they learned. For instance, Jacques Gravier, vicar general of the Illinois Mission

in the Mississippi River valley, compiled the most extensive Kaskaskia Illinois-French dictionary

among works of the missionaries before his death in 1708.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Society_of_Jesus#Expansion

The chapel at St. Francis Xavier Church holds relics that are supposed to be of the

most sacred to Christianity in Asia, believed to be bone fragments of St. Francis

Xavier himself that were originally bound for Japan but ended up in Macau.

Watch Trailer

The Mission is based on events surrounding the Treaty of Madrid in 1750, in which Spain ceded

part of Jesuit Paraguay to Portugal. A significant subtext is the impending Suppression of the

Jesuits, of which Father Gabriel is warned by the film's narrator, Cardinal Altamirano, who was

once himself a Jesuit. Altamirano, speaking in hindsight in 1758, corresponds to the actual

Andalusian Jesuit Father Luis Altamirano, who was sent by Jesuit Superior General Ignacio

Visconti to Paraguay in 1752 to transfer territory from Spain to Portugal. He oversaw the

transfer of seven missions south and east of the Río Uruguay, that had been settled by Guaranis

and Jesuits in the 17th century. As compensation, Spain promised each mission 4,000 pesos, or

fewer than 1 peso for each of the circa 30,000 Guaranis of the seven missions, while the

cultivated lands, livestock, and buildings were estimated to be worth 7-16 million pesos. The

film's climax is the Guarani War of 1754-1756, during which historical Guaranís defended their

homes against Spanish-Portuguese forces implementing the Treaty of Madrid. For the film, a recreation

was made of one of the seven missions, São Miguel das Missões.

Father Gabriel's character is loosely based on the life of Paraguayan saint and Jesuit Roque

González de Santa Cruz. The story is taken from the book "The Lost Cities of Paraguay" by

Father C. J. McNaspy, S.J., who was also a consultant on the film.

The waterfall setting of the film suggests the combination of these events with the story of older

missions, founded between 1610-1630 on the Paranapanema River above the Guaíra Falls, from

which Paulista slave raids forced Guaranís and Jesuits to flee in 1631. The battle at the end of

the film evokes the eight-day Battle of Mbororé in 1641, a battle fought on land as well as in

boats on rivers, in which the Jesuit-organized, firearm-equipped Guaraní forces stopped the

Paulista raiders.

The relic of St Francis Xavier coming to Australia is his right arm. This is the arm with which

he baptized and blessed thousands of people, the hand with which he tended and held so many

sick and dying people, with which he wrote letters back home to his companions, reporting his

adventures, trials and triumphs of ministry, and inspiring many others to be engaged in the

missionary enterprise.

Xavier was buried on Shangchuan Island after his death, but his body was moved to Malacca two

months later, at which time it was found to be incorrupt. From the start, miracles were

associated with this relic. From the moment of its arrival in Malacca, the plague which had been

raging there abruptly ceased, blind people were given their sight and sick people were healed.

After nine months, it was moved to Goa, the scene of Xavier's original and highly successful

missionary work. It remains there to this day, in the Basilica of Bom Jesus. Every ten years

Xavier's body is exposed for veneration, and in 2005, over 2 million people came to honour him.

In 1614, the Superior General of the Jesuits arranged for the right forearm to be detached so

that this significant relic could be an object of devotion at the main Jesuit church in Rome, the

Gesú. This relic has only been allowed to be removed from the Gesú on a small number of

occasions, and so we are very blessed to have this opportunity in Australia for our Year of

Grace.

See printed copy.

Religious Division of Europe After the Reformation (16th Century)

http://staff.jccc.edu/jjackson/reformation.htm