5. Christian world views through the centuries

Lesson Objectives:

In this lesson we will discuss:

- how the notion of a "Christian world view" has changed through the centuries

- why is it is important to understand the context in which people live when defining how the Christian world view can be incarnated

Grappling with major issues as a believer with a "Christian world view" is not new, but the way it has been expressed has changed a lot over the centuries. Since the days of Jesus Christ, His followers have been called into Kingdom living, but have operated in (very) different circumstances, cultures, experiences and outlooks than ours. The challenge for individual Christians is to understand how to contextualise without syncretism.

We will look at several case studies of Christian world views through the centuries. Put yourself in their skin, in their shoes; try to imagine how they lived and thought, the issues they faced and the challenges that existed as they sought to live by the theme "What would Jesus do?"

1. A Greek Christian in First Century Corinth

Christians in this era lived during the "incubation" of the church; everything "Christian" was new.

The dominant world view in ancient Corinth was Greek culture, polytheism and philosophy (lit. love of wisdom). Corinthian Christians were first-generation believers; the first who left their pagan roots (see 1 Corinthians 6:10, 11) and (often) social structures. Christianity was seen by many as a sect of Judaism, their deity the "Jewish god". Judaisers sought to impose Jewish laws on converts. Gentiles did not generally understand the inner working of Jewish monotheistic/ nationalistic theology (although there were Jewish converts in many societies). They had no New Testament, no clergy and no church buildings. The Lord's Supper (based on a Jewish festival, Passover) was a regular feature of worship. Greek society, on the other hand, was littered with gods (the most famous being Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Artemis, Poseidon, Aphrodite, Athena, Demeter, Hermes Ares and Hades; there were many others: Asclepius, the god of medicine, Persephone, Demeter's daughter, Gaia the earth goddess, Hecate, and so forth; in addition, every village had its own gods.) Corinthian Christians lived in a polytheistic world that therefore regarded (and persecuted) them as atheists.

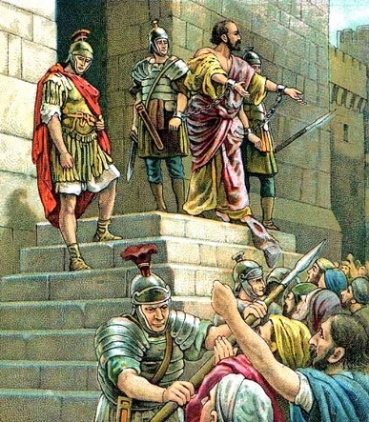

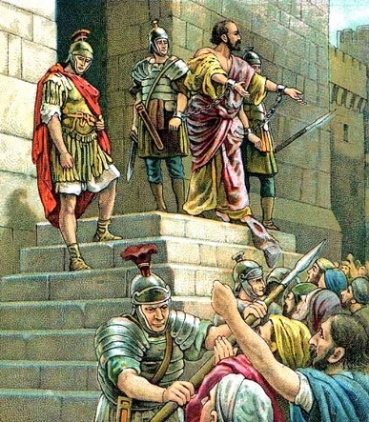

Paul in Corinth - see Acts 18 for details

Paul in Corinth - see Acts 18 for details

Christians in Corinth had the advantage of hearing from people who were eyewitnesses of Jesus' life, death and resurrection and the birth of the church. They had a strong expectation of the return of Christ and the destruction of the dominant world order; in this respect they were regarded as overt challenges to tradition, and to city authority and security.

Christian preaching, belief in life after death (including as consolation for poor quality of life now), forgiveness of sins (a powerful incentive in an age where gods normally resorted to punishment rather than forgiveness), the Fatherhood of God, inclusive family of God, eternal rewards for godly living, hope for the return of Christ, gave hope and security found nowhere else. The Christian community provided a strong network. Feasts gave structure and order for new converts. By the beginning of the second century, interpretations of the Revelation led to expectations that the world order was about end.

Much of the appeal of Christianity was the way it helped the poor and needy (there were no pensions or dole to support the aged or those without work or support), Christians ministered to the sick, reached out to the suffering during epidemics, became known for their work during epidemics such as plague, smallpox, measles, when thousands died and others fled for their lives; pagan religions usually offered little consolation or support), Christians taught love, compassion, acceptance and equality before God.

Discussion: what else would have been the world view of a Christian in this early period?

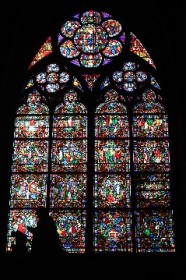

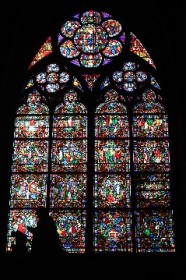

2. A Peasant in a Cathedral in France during the Black Death

As the 14th century dawned, "Christendom" was an established system, based on a nexus of political and ecclesiastical power in Europe. Society was highly regulated by the church. Most peasants (and often their rulers) during the Middle Ages were illiterate. Ninety per cent were agrarian. The better educated in society belonged to the church (monks, priests). Peasants (or "serfs") worked on their lords' manorial grounds; part-time for themselves, the remainder for the benefit of their owners. The church demanded at least a tithe of all produce. Serfs were generally not mobile (being forbidden from leaving their estates). They lived a subsistence lifestyle, a daily struggle for survival that that left little margin for famine or disease. Apart from feast days and Sundays the only exposure to what Christians taught came from sermons and stain glass windows in churches. Church liturgy and the Bible (the Vulgate, but not the vernacular) were in Latin. Belief was highly regulated and divergence was generally not tolerated.

Peasants knew that, beyond their ramshackle dwellings, filth, hardship and short lives, lay the village church or cathedral (over 100 cathedrals were built between 1100-1500) that promised a better future life. "Credo in unum Deum...." They assumed everyone was a "Christian".

The 14th Century was a time of widespread fear, turmoil, loss of confidence in institutions (including the established church), and feelings of helplessness in the face of life-threatening events. Much of Europe suffered a mini ice age in the early 1300s. In France, crops failed after heavy rains in 1315; there were widespread famines and reports of cannibalism; and France was involved in a series of military campaigns against the English, known as the Hundred Years War.

Epidemics were common; the best known of these was the Black Death (1346-1353), which killed an estimated third of the total population from India to Iceland. It spread quickly. People usually had nowhere to go, no other means to sustain themselves, they were quite fatalistic.

The Black Death was caused by fleas carried by rats that were common in towns/cities. The fleas bit their victims, injecting them with the disease. Death could be very quick. The first signs of the plague were lumps (or buboes) in the groin or armpits. After this, black spots appeared on the arms and thighs and other parts of the body. Few recovered. Almost all died within two to three days. The oldest, youngest and poorest died first. Others died from personal contact with the sick (septicemia) or water droplets through coughing or sneezing (pneumatic).

Entire villages simply ceased to exist. Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims and lepers were blamed and persecuted, adding to widespread fear and misery. In Spain, Arabs were suspected of spreading plague. In towns, people lived close together, in unhygienic conditions, and knew nothing about contagious diseases. The disposal of bodies was crude and helped to spread the disease further as those who handled dead bodies did not protect themselves in any way. The filth that littered streets gave rats the perfect environment to breed and increase their number.

Entire villages simply ceased to exist. Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims and lepers were blamed and persecuted, adding to widespread fear and misery. In Spain, Arabs were suspected of spreading plague. In towns, people lived close together, in unhygienic conditions, and knew nothing about contagious diseases. The disposal of bodies was crude and helped to spread the disease further as those who handled dead bodies did not protect themselves in any way. The filth that littered streets gave rats the perfect environment to breed and increase their number.

Lack of medical knowledge meant that people tried anything to help them escape the disease. One of the more extreme was the flagellants, who travelled from town, demonstrating their love of God by whipping themselves, hoping that He would forgive their sins and spare them. Others carried flowers hoping that the perfume would ward off bad "humours" that were thought to spread disease.

Society was in turmoil. Fields went unploughed as labourers died. Entire villages faced starvation as crops failed or were simply not planted. Towns and cities experienced food shortages as the villages that surrounded them could not provide them with enough food. The crime rate in many cities soared, as people cast off restraint, abandoned order and traditional moralities because they believed they were doomed anyway.

The Black Death was a challenge to the prestige and spiritual authority of the organized Church, while at the same time there was a marked growth in religious enthusiasm and birth of marginal groups. The church (many of whose own monks and priests had perished in the plague) could offer no reason for the deadly disease and beliefs were tested. People started questioning religion.

Where was the God of the soaring, breathtakingly beautiful cathedrals God in all this? What view did ordinary peasants have about the Christian message? Everyone in those days believed in God, but it seemed that God did not answer their cries for help and security. Genuine Christian believers existed, but their approaches to a Christian world view were impacted by their language, culture, economic status, political power, kinship bonds, other relationships, levels of education and the integrity of local church leadership.

Discussion: how might the average Christian have coped in this profoundly uncertain period?

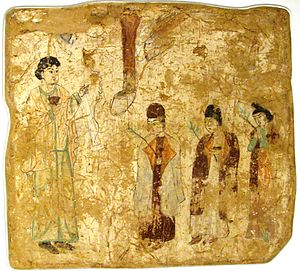

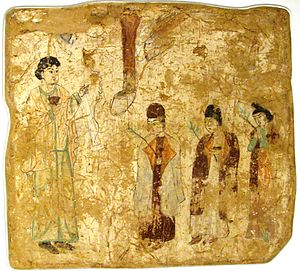

3. A Nestorian Believer in China

In 431 AD the Council of Ephesus condemned the teachings of Nestorius, Bishop of Constantinople from 428-431, in particular in relation to the role of Mary. Nestorius had argued that Mary be titled the Christotokos, or "Birth Giver of Christ"; the majority of the Council argued for Theotokos, "Birth Giver of God". (What's more, Nestorius did not accept the concept of Jesus having both human and divine natures in one.) His sermons and teachings were ordered to be burned.

Early Nestorians fled persecution in the Christian Roman Empire and settled in Sassanid Persia, where they affiliated with the local Christian community and became known as the Church of the East. They subsequently evangelized as far afield as China (Nestorians were in Mongolia at the time of Ghengis Khan), Siberia, Afghanistan, Japan and India. Not only did they spread the Gospel and plant churches but they also developed written languages for many cultures they encountered. Some historians estimate the number of Nestorian Christians was twice that in the West. The two movements were largely separated by Persia.

In the late 1200s, Kubla Khan, the Mongol ruler of China, met representatives of Roman Catholicism: Marco Polo and his uncles. Kubla Khan was so intrigued, he sent the uncles back to Rome with an invitation for the pope to send 100 "teachers of science and religion" who would try to prove "that the faith professed by Christians is superior to and founded on more evident truth than any other." Twenty years passed before a single Franciscan was sent. He was received by Kubla Khan's successor and within a short time established churches in several cities and translated the New Testament and Psalms into the language of the court. There were major differences between Nestorian and Catholic leaders. However, under the Ming dynasty, Christians in China were subject to repression that lasted over a century. By the late 1500s, there were, as far as we know, no churches left.

Discussion: what would have been the world view of a Christian in central Asia in this turbulent period? What could they have done differently?

4. A Monk in a Monastery during the Viking Era

"This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island, by rapine and slaughter."

(Entry for the year 793 in the Anglo Saxon chronicle.)

"This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island, by rapine and slaughter."

(Entry for the year 793 in the Anglo Saxon chronicle.)

Early Christian monastics sought to follow the examples of Elijah and John the Baptist, who lived alone for periods in desert places and went without basic comforts. Some early Christian leaders sought to follow in the steps of Jesus, who spent time alone in the desert after his baptism. They renounced positions and possessions (taking as their inspiration Jesus' command to the rich young ruler in Luke 18:22), left their homes, adopted celibacy (or abstinence) and lived as ascetics in remote places, where they prayed, meditated at length on the Bible and faith, worshipped, fasted, sought to deepen their communion with God and their dependence on Him (citing Matthew 6:25-34) and trained disciples.

From very early days, pilgrims came to sit at the feet of religious masters, returning home to spread what they had learned; some monks were believed to have special access to God and be able to perform miracles.

In 793, the Christian community on the island of Lindisfarne (on an island off the north-east coast of England, seat of a prior, then monastery, since the 7th century and a base for Christian evangelising in the North of England) was sacked by Viking invaders. The monks were robbed and murdered. Had God let them down in spite of their faithfulness?

The Vikings were a seafaring people who originated in modern-day Denmark and Norway. In the 700s, pressure on land in Scandinavia forced nobles and warriors to seek land elsewhere. They were feared throughout Europe because they killed anyone who got in their way or took them as slaves.

In 795 AD Viking long ships began to raid monasteries along the coast of Ireland. Christian monasteries had often been positioned on small islands and in other remote coastal areas so that the monks could dwell there in seclusion, devoting themselves to worship without the interference of other elements of society. At the same time, it made them isolated and unprotected targets for attack; their wealth was seen as a fair target.

Discussion: what would have been the world view of a Christian facing Viking threats? How hard might it have been to believe that the descendants of the Vikings would become the Normans and rule a "Christian" England?

5. A "Christian" in Palestine during the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of wars waged by Christian Europe, in the name of Jesus Christ, against Muslims occupying the Holy Land.

Since the time of Constantine, Christians had made pilgrimages to the Holy Land. Following the capture of Jerusalem by Caliph Omar in 637, Jerusalem had been governed by Muslims, but they tolerated Christian pilgrims because they helped the economy (eg by paying additional taxes).

In the 1070s, Seljuk Turks (also Muslims) conquered the holy lands and mistreated Christians. They threatened the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Alexius asked the Pope for assistance, and Pope Urban II, seeing a way to harness the energy of Christian knights, made a speech calling for them to take back Jerusalem. Thousands responded, resulting in the First Crusade. All crusaders believed that they were "true Christians".

There were as many different reasons for crusading as there were crusaders. The most common reason was piety. To crusade (lit. to "take the cross") was to go on pilgrimage, a holy journey to obtain personal salvation, in the hope of pleasing God and earning eternal life. To many this meant giving up virtually everything and willingly facing death for God. For those willing to do so the church offered "absolution" for all kinds of sin, eternal bliss (especially for martyrs who died in defending the cause of Christ), miracles for participants and their family members back home, cancellation of debts, pardons for convicted criminals and escape from feudal lords.

For thousands of ordinary people going on crusade meant a way out of grinding poverty and serfdom in Europe. For others it created opportunities to indulge in blood lust without guilt, or seek adventure, gold or personal glory. When crusader armies defeated the ancient cities in Palestine they slaughtered Muslims, Jews and local Christians indiscriminately. Hundreds of thousands volunteered for the Crusades; thousands perished believing they were doing God's work.

For thousands of ordinary people going on crusade meant a way out of grinding poverty and serfdom in Europe. For others it created opportunities to indulge in blood lust without guilt, or seek adventure, gold or personal glory. When crusader armies defeated the ancient cities in Palestine they slaughtered Muslims, Jews and local Christians indiscriminately. Hundreds of thousands volunteered for the Crusades; thousands perished believing they were doing God's work.

Discussion: what would have been the world view of a "Christian" in this period of contradiction? Many Muslims continue to believe the crusaders were Christians (look at the cross on their shields) and remember the atrocities they conducted in Christ's name.

6. An Orthodox Adherent in Constantinople in 1450

The Great Schism divided Christianity into Western (Roman) Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. In 1054 Pope Leo IX and Byzantine Patriarch Michael I excommunicated each other. The split was the result of an extended period of estrangement between the two branches of the church. Root causes included arguments about papal authority, the insertion of the "filioque clause" (related to the coming of the Holy Spirit) into the Nicene Creed, and linguistic, cultural, political and liturgical differences. Orthodox believers emphasized the reign of Christ (rather than concentrating on his passion). Orthodox worship services focused on Christ.

The Byzantine capital, Constantinople, was sacked by "Christian" crusaders in 1204. (Latin) Catholics considered Orthodox Christians heretics (outside the true church) and therefore legitimate "non-Christian" targets. Constantinople, thus weakened, was vulnerable to ongoing attacks from Crusaders and Muslims alike.

Christians in this period followed the teachings of the Orthodox leadership, believed in the security of mother church, who in turn reflected the political structures, whom they hoped would keep them safe, in the context of gradual encirclement of Constantinople by Turkish armies. Christian cities in other parts of the region had been razed, followers of Christ put to death or forcibly converted to Islam; many had been enslaved. Churches contained icons, which adherents venerated, but churches in the West opposed (on and off). The largest church was the great Hagia Sofia; built in 537, but in the 1400s the Byzantine world seemed about to collapse. Was this the end of the world? (Constantinople finally fell to Muslim forces in 1453.)

Discussion: what would have been the world view of a Christian in this period of betrayal and fear for the future?

7. An Anabaptist in Zurich during the Protestant Reformation

The Anabaptist movement started in Europe about 1525. Anabaptists believed in adult baptism, as opposed to baptism of infants. Originally used as a derogatory term, Anabaptist meant "re-baptizer," because some of these believers who had been baptized as infants were baptized again. Those so baptized regarded it as their first (real) baptism. The Anabaptists believed that a person can only be legitimately baptized only when they are old enough to give informed consent. They called the act "believer's baptism." Re-baptism was a crime punishable by death at the time, eg by drowning (as a mockery of their focus on the water of baptism).

Anabaptists refused to take oaths and taught the separation of church and state. They rejected the concept of "Christendom" as a political/social entity. They preached simple worship, removed pictures and statues from churches and emphasized holiness and the power/authority of the Word of God. Anabaptists believed that infants are not punishable for sin until they become aware of good and evil and can exercise their own free will, repent, and accept baptism.

Anabaptists were evangelical but were opposed by official protestant denominations. Thousands were executed by reformist church leaders. They were also opposed because they were pacifists. They sought a return to apostolic Christianity and radical discipleship by the individual believer. Anabaptists believed that Christianity involved a personal daily walk with God, and a transformed life based on obedience to Christ. Anabaptists believed in congregational church government.

Discussion: what would have been the world view of a Christian in this period, amid the turmoil of the Reformation, differing views as to baptism, the Lord's Supper, ecclesiastical government, the role of the church in civil society and scope for variations in doctrinal positions?

8. A Moravian believer in the West Indies

Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf was born in 1700 into wealth and a noble family. As a young man, he developed a passion for spreading the gospel. He attended Wittenberg University with the aim of earning a law degree, but felt a call to serve Christ. In 1719 he was impacted by a painting of Christ wearing a crown of thorns. An inscription below the painting read, "All this I did for you, what are you doing for me?" This was a decisive moment in his life, moving him to enter Christian ministry. On 13 August 1727, during a communion service on Zinzendorf's estate (Hernut, Germany), the Holy Spirit moved powerfully. Zinzendorf led others (many of them Hussite refugees) in a prayer meeting that lasted one hundred years. Beginning with a deep conviction for reaching the world with the Gospel, the meeting deepened in passion for the lost. This was undeniably the force behind the great Moravian missions movements that followed.

"The simple motive of the brethren for sending missionaries to distant nations was and is an ardent desire to promote the salvation of their fellow men, by making known to them the gospel of our Savior Jesus Christ. It grieved them to hear of so many thousands and millions of the human race sitting in darkness and groaning beneath the yoke of sin and the tyranny of Satan; and remembering the glorious promises given in the Word of God, that the heathen also should be the reward of the sufferings and death of Jesus; and considering His commandment to His followers, to go into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature, they were filled with confident hopes that if they went forth in obedience unto, and believing in His word, their labor would not be in vain in the Lord. They were not dismayed in reflecting on the smallness of their means and abilities, and that they hardly knew their way to the heathen whose salvation they so ardently longed for, nor by the prospect of enduring hardships of every kind and even perhaps the loss of their lives in the attempt. Yet their love to their Saviour and their fellow-sinners for whom He shed His blood, far outweighed all these considerations. They went forth in the strength of their God and He has wrought wonders in their behalf."

The first two (of hundreds) Moravian missionaries sailed for the West Indies on 8 October 1732. Their purpose was to follow Jesus' command, "As the father has sent me so send I you." The only way to reach slaves in the West Indies was to become incarnated into their lives. They therefore sailed with the objective of selling themselves into slavery to reach slaves with the Gospel.

When Moravians reached their destinations, they would unload their belongings and burn their ships, refusing to look back or abandon their goal of evangelisation.

Discussion: what would have been the world view of a Christian in this period of growing (but personally costly) world mission? "What would Jesus do" reaching slaves in the West Indies by becoming one of them (cf Philippians 2:7).

9. A Lutheran in Germany During the Rise of Adolf Hitler

Christianity in Germany during the first half of the 20th century faced enormous pressures in terms of scholarship, liberalism, the impact of World War I and the Great Depression, the growth of communism and the rise of National Socialism (Nazism) that eventually co-opted the Christian community as part of the official state structure.

Evangelical Christian leaders in Germany believed that they were to be "in the world, but not of it" and did not conform to the new state-controlled church.

Anti-Jewish Nazi ideology was characterized by strong anti-Semitism that some saw as having roots in Christian history. For many Christians, tradition supported these prejudices. Large numbers of clergy and theologians sided with the Nazi regime.

Over time, anti-Nazi sentiment grew in both Protestant and Catholic Church circles, as the Nazi regime exerted greater pressure on them. When a protest statement was read from the pulpits of Confessing churches in March 1935 the Nazi authorities reacted forcefully by briefly arresting over 700 pastors; this pattern of intimidation continued.

The attitudes and actions of German Catholics and Protestants during the Nazi era were shaped not only by their religious beliefs, but by politics, nationalism, prejudice and fear.

Many Lutheran pastors in Germany during the rise of Hitler were forced to make a choice between accepting state control of the church or continuing their evangelical tradition. Well-known Swiss theologian Karl Barth refused to submit, lost his teaching position in Bonn for refusing to submit to the pro-Nazi "German Christians" and swear an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler, and returned to Switzerland.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was born in 1906, son of a professor of psychiatry and neurology at the University of Berlin. He was an outstanding student, and at the age of 25 became a lecturer in systematic theology at the same University.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Bonhoeffer became a leading spokesman for the Confessing Church, the centre of Protestant resistance to the Nazis. He organized and for a time led the underground seminary of the Confessing Church. His book The Cost of Discipleship identifies what he called "cheap grace," meaning grace used as an excuse for moral laxity. Bonhoeffer had been taught not to "resist the powers that be", but he came to believe that to do so was sometimes the right choice (he had been officially forbidden to preach or publish his works in Germany). That choice meant leaving (safer) England and returning to Germany to help lead the Christian community at a time of difficult choices: to obey God or the state.

Bonhoeffer was arrested in April 1943 after being accused of helping smuggle Jews out of Germany to safety in Switzerland and was imprisoned in Berlin. After the failure of an attempt on Hitler's life in April 1944, he was sent to Buchenwald, then to Schoenberg Prison. His life was spared, because he had a relative in the government; but then this person was implicated in anti-Nazi plots.

On 9 April 1945, Bonhoeffer was hanged, less than a week before the Allies reached the camp.

Discussion: what would have been the world view of a Christian during this dark period? What would Jesus have done in the face of the popular Nazi movement that some churches openly supported?

10. A Sisters of Mercy Nun in Calcutta

In 1948 Mother Teresa received permission from Pope Pius XII to live as an independent nun, in Calcutta.

She rented a small hovel to begin her work. Though she had no equipment to begin with, she made use of what was available - writing in the dirt.

Mother Teresa strove to make the children of the poor literate and teach them hygiene. She gradually began visiting the poor and ill where their families crowded together in the surrounding squalid shacks. She ministered to poor living on the streets. Mother Teresa found a never-ending stream of human needs in the poor she met, and was frequently exhausted. Despite the weariness of her days, and times of doubt (documented at the time and debated since), she never neglected her prayer life, finding it the source of support, strength and blessing for all her ministry.

Until her death in 1997 she served those in great need wherever they were found. Homes for the dying, refuges for the care and teaching of orphans and abandoned children, treatment centres and hospitals for those suffering from leprosy, centres and refuges for alcoholics, the aged and street people; the poverty of Calcutta and cities like it is grinding and often only Christians were willing to offer help to those most in need. The only "Jesus" people in the street saw were Mother Teresa and members of her community.

Listen to her words: "At the end of life we will not be judged by how many diplomas we have received, how much money we have made, how many great things we have done. We will be judged by 'I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat, I was naked and you clothed me. I was homeless, and you took me in.' " (Matthew 25:35, 36)

Listen to her words: "At the end of life we will not be judged by how many diplomas we have received, how much money we have made, how many great things we have done. We will be judged by 'I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat, I was naked and you clothed me. I was homeless, and you took me in.' " (Matthew 25:35, 36)

".... after we had removed the worms from his body, all he said, with a big smile, was: 'Sister, I am going home to God' -and he died. It was so wonderful to see the greatness of that man who could speak like that without blaming anybody, without comparing anything. Like an angel - this greatness of people who are spiritually rich even when they are materially poor. We are not social workers. We may be doing social work in the eyes of some people, but we must be contemplatives in the heart of the world. For we are touching the body of Christ and we are always in his presence. ...... I want you to find the poor here, right in your own home first. And begin love there. Bear the good news to your own people first. And find out about your next-door neighbours. Do you know who they are?" (Mother Teresa, National Prayer Breakfast, Washington, 1994).

Discussion: what would have been the world view of a Christian ministering on the streets of Calcutta during this period? Reaching out to Hindus and Muslims, when no one else wanted to do so. What prevented Christians in other parts of the world from following Mother Teresa's example? What prevents us today?

We could talk about other case studies, eg

- a committed Christian woman whose husband was in the World Trade Centre on 11 September 2001

- a Pentecostal girl in Nigeria kidnapped by Boko Haram in 2014

- an Iraqi mother watching her church being destroyed by Islamic State forces in 2015

Issues: given these stories from history (and some additional contemporary examples), what is an authentic Christian world view? Not just a theoretical framework, but a real way of thinking, in the life and death contexts described?

In every age, God has had people who have remained faithful to the true Gospel. What about the rest? Were they genuine Christians? Has each generation simply reinterpreted Christ to fit its needs? How might we have responded to the challenges they faced? How does their example impact the way we see our place in the world today?

From Nestorian missionaries to modern China

Paul in Corinth - see Acts 18 for details

Paul in Corinth - see Acts 18 for details

Entire villages simply ceased to exist. Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims and lepers were blamed and persecuted, adding to widespread fear and misery. In Spain, Arabs were suspected of spreading plague. In towns, people lived close together, in unhygienic conditions, and knew nothing about contagious diseases. The disposal of bodies was crude and helped to spread the disease further as those who handled dead bodies did not protect themselves in any way. The filth that littered streets gave rats the perfect environment to breed and increase their number.

Entire villages simply ceased to exist. Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims and lepers were blamed and persecuted, adding to widespread fear and misery. In Spain, Arabs were suspected of spreading plague. In towns, people lived close together, in unhygienic conditions, and knew nothing about contagious diseases. The disposal of bodies was crude and helped to spread the disease further as those who handled dead bodies did not protect themselves in any way. The filth that littered streets gave rats the perfect environment to breed and increase their number.

"This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island, by rapine and slaughter."

(Entry for the year 793 in the Anglo Saxon chronicle.)

"This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island, by rapine and slaughter."

(Entry for the year 793 in the Anglo Saxon chronicle.)

For thousands of ordinary people going on crusade meant a way out of grinding poverty and serfdom in Europe. For others it created opportunities to indulge in blood lust without guilt, or seek adventure, gold or personal glory. When crusader armies defeated the ancient cities in Palestine they slaughtered Muslims, Jews and local Christians indiscriminately. Hundreds of thousands volunteered for the Crusades; thousands perished believing they were doing God's work.

For thousands of ordinary people going on crusade meant a way out of grinding poverty and serfdom in Europe. For others it created opportunities to indulge in blood lust without guilt, or seek adventure, gold or personal glory. When crusader armies defeated the ancient cities in Palestine they slaughtered Muslims, Jews and local Christians indiscriminately. Hundreds of thousands volunteered for the Crusades; thousands perished believing they were doing God's work.

Listen to her words: "At the end of life we will not be judged by how many diplomas we have received, how much money we have made, how many great things we have done. We will be judged by 'I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat, I was naked and you clothed me. I was homeless, and you took me in.' " (Matthew 25:35, 36)

Listen to her words: "At the end of life we will not be judged by how many diplomas we have received, how much money we have made, how many great things we have done. We will be judged by 'I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat, I was naked and you clothed me. I was homeless, and you took me in.' " (Matthew 25:35, 36)